PREFACE

This is the Fourth Edition of the Guide, which we have produced for the information of our clients and professional colleagues. This edition takes account of changes brought about by the Companies Act 2001 and the Financial Services Act 2007.

This Guide is divided into five parts:

1. Mauritian Companies

2. Foreign Companies in Mauritius

3. Compromises with Creditors, Arrangements, Amalgamations and Minority Buy-out Rights

4. Mergers and Takeovers

5. General Information

Under the heading of General Information, we have dealt with matters such as banking facilities in Mauritius, accountants, registers and inspection, and other topics.

This Guide is concerned primarily with "global business companies" and "foreign companies"; little reference has, therefore, been made to those provisions of the Companies Act 2001 which regulate the carrying on of business by domestic companies in Mauritius.

All references in this Guide to "dollars" or "$" are to US dollars, and all references to "rupees" or "Rs" are to Mauritian rupees.

It is recognised that this Guide will not completely answer detailed questions which clients and their advisers may have. It is intended to provide a sketch of Mauritius' legal and regulatory environment in relation to exempted and permit companies. The Guide is, therefore, designed as a starting-point for a more detailed and comprehensive discussion of the issues.

Whilst we have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the statements made herein, we accept no liability for any errors. In all cases expert legal advice from a qualified practitioner of Mauritius law should be obtained.

INTRODUCTION

Mauritius' statute law on companies is contained in the Companies Act 2001 (the "Companies Act"), which was modelled after its counterpart from New Zealand. The Law Commission endorsed the view that: (i) the enabling function of the company law should be seen as a standard contract that reduced the costs of organising a business enterprise; and (ii) the regulatory function should protect against abuse of management power while providing protection for minority shareholders and creditors where the market failed. The goal was for the regulation of corporate activity to be commensurate with the real danger of abuse while not inhibiting legitimate business activity. The Law Commission determined that the most appropriate legislation would be primarily enabling in form, rather than regulating, except where the risk of abuse was clear, and from these principles the Companies Act was formed. The Companies Act has been regularly amended by the legislature to keep track of the changes in law having an incidence on Mauritius incorporated companies.

All references, however, to legislative provisions herein are to the Companies Act 2001, unless otherwise stated.

PART A: MAURITIAN COMPANIES

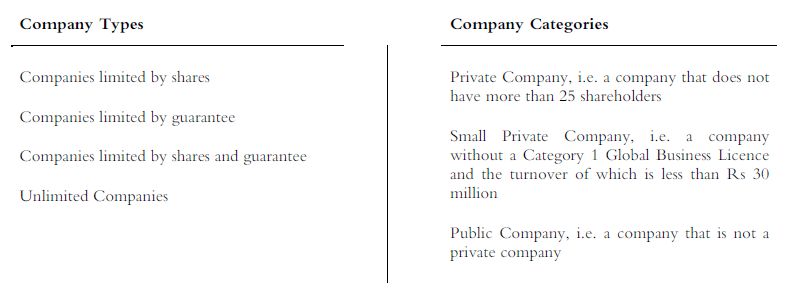

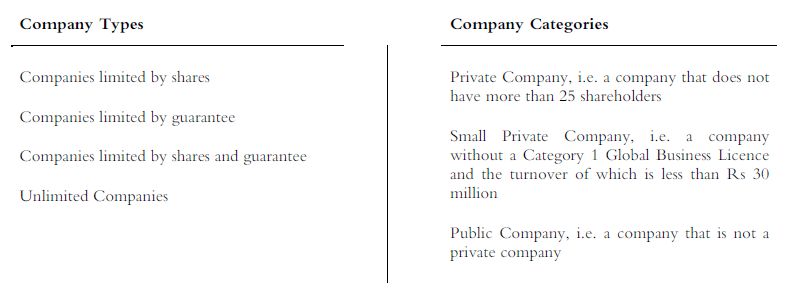

1. Classification

The Companies Act provides for several types and categories of companies (§21(2)):

It should be noted that the Companies Act provides the possibility for a foreign company to register in Mauritius. Companies may also be set up in Mauritius as Limited Life Companies.

The now repealed Financial Services Development Act 2001 (the "FSDA") first introduced in Mauritius the concept of: (i) "qualified global business", defined as being any business or other activity carried out from Mauritius, by any entity, preferably corporate in nature, with persons ordinarily resident outside Mauritius and conducted in a currency other than the Mauritius Rupee; and (ii) "global business companies," being companies holding either a Category 1 (formerly Offshore Companies) or a Category 2 (formerly International Companies) Global Business Licence (a "GBL") eligible to conduct qualified global business from Mauritius. The FSDA has now been repealed by the FSA, which has revamped the meaning of qualified global business, now referred to as "Global Business". Any resident corporation which proposes to conduct business outside Mauritius may apply to the Financial Services Commission (the "Commission") for a Category 1 Global Business Licence or a Category 2 Global Business Licence. However, nothing shall prevent a Category 1 Global Business Licence from doing any of the following:

- conducting businesss in Mauritius;

- dealing with a person resident in Mauritius or with a corporation holding a Category 2 Global Business Licence; or

- holding shares or other interests in a corporation resident in Mauritius.

Dormant companies are solely mentioned within the context of this Guide as they are exempt from having their accounts audited and from paying certain fees, although they must still file accounts and returns as required under the Companies Act. A dormant company is defined as having no significant accounting transactions (excluding payment of bank charges, licence fees and compliance costs, if any) over an extended period of time (§293), but a company may also declare itself dormant upon passing a special resolution (§294). The company must then file the resolution with the Registrar of Companies (the "Registrar") at the Division of Companies within 14 days of the date of the resolution (§294(3)).

a. Category 1 Global Business Licence

An application for a Category 1 Global Business Licence (a "GBL1") may only be made through a management company in such form as may be approved by the Commission (§72(1) FSA).

Any entity holding a GBL1 is allowed to undertake from within Mauritius any business activity which is not illegal or against public policy and which would not cause prejudice to the good repute of Mauritius as a centre for financial services (§72(4) FSA). A further licence will need to be obtained by the company if it is to carry on financial or investment services.

In considering an application for or a renewal of a GBL1, the Commission shall have regard to whether the conduct of business will or is being managed and controlled from Mauritius. In determining whether the conduct of business will be or is being managed and controlled from Mauritius, the Commission shall have regard to such matters as it may deem relevant in the circumstances and without limitation to the foregoing may have regard to whether the corporation (§71(4) FSA):

- shall have or has at least two directors, resident in Mauritius, of sufficient calibre to exercise independence of mind and judgment;

- shall maintain or maintains at all times its principal bank account in Mauritius;

- shall keep and maintain or keeps and maintains, at all times, its accounting records at its registered office in Mauritius;

- prepare or proposes to prepare its statutory financial statements and causes or proposes to have such financial statements to be audited in Mauritius; and

- provides for meetings of directors to include at least two directors from Mauritius.

Applications to the Commission can only be submitted through a duly licensed management company and must be accompanied by the prescribed processing fees, a law practitioner's certificate certifying that the application complies with the laws of Mauritius and any other information which the Chief Executive of the Commission may request (§72 FSA).

In addition to companies, trusts, partnerships (including a limited partnership or a "societe") and Foundations may apply for a GBL1. With regards to companies, both public and private companies in Mauritius, as well as foreign companies, may apply for a GBL1.

A company may apply for a GBL1 concurrently with the incorporation process. Once incorporated and the applicant has accepted any conditions as may be laid down by the Commission, the latter shall then issue the GBL1 after the payment of the prescribed licence fee, which is renewable every year.

A GBL1 may also be applied for upon the registration in Mauritius of a branch of a foreign company (or even by way of continuation where allowed by law in the country of origin). The branch of a foreign company may then have access to the various tax treaties available through Mauritius, provided the Commissioner of Tax is adequately satisfied that effective control and management of the foreign company is in Mauritius. The opportunity for continuing a company originally registered in a foreign jurisdiction with a GBL1 allows the foreign company to benefit from relief on its existing holdings if that country has a double taxation treaty with Mauritius.

GBL1 holders qualify for protection under the various tax treaties to which Mauritius is a party, provided they fall within the definition of "resident" under the taxation laws of Mauritius. In order to satisfy this requirement, the company will need to have its central management and control in Mauritius.

A GBL1 company is generally required to file with the Commission its annual audited financial statements within six months after the close of its financial year, prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards and audited in accordance with the International Standards on Auditing, and such other standards as may be acceptable under the Financial Reporting Act 2004, by an audit firm approved by the Commission.

A GBL1 company must have a minimum of one company secretary, who must be a natural person ordinarily resident in Mauritius, although a corporation may act as secretary with the approval of the Registrar and subject to certain specified conditions.

Our associated licensed management company, Appleby Management (Mauritius) Ltd. Offers corporate administrative, secretarial and resident representative services.

b. Category 2 Global Business Licence

An application for a Category 2 Global Business Licence (a "GBL2") may only be made through a management company in such form as may be approved by the Commission (§72(1) FSA).

Any entity holding a GBL2 is allowed to undertake from within Mauritius any activity other than those activities listed in the Fourth Schedule of the FSA, which are:

- banking;

- financial services (see Schedule 1 of this Guide for a full list of "financial services");

- carrying out the business of holding or managing or otherwise dealing with a collective investment fund or scheme as a professional functionary;

- providing of registered office facilities, nominee services, directorship services, secretarial services or other services for corporations;

- providing trusteeship services by way of business.

A significant difference between a GBL1 and a GBL2 is that a GBL2 holder is exempted from the provisions of the Income Tax Act 1995 (the "Income Tax Act") and is deemed to be 'non-resident' for tax purposes.

A GBL2 provides for greater flexibility and it is a suitable vehicle for holding and managing private assets. However it is not allowed to raise capital from the public or to conduct any financial services or to act as a fiduciary.

Under the FSA, only private companies may apply for a GBL2 (§71(3) FSA). Like an application for a GBL1, it must be accompanied by the incorporation documents and a law practitioner's certificate certifying that the application complies with the laws of Mauritius.

Once the company is incorporated and the applicant signifies his acceptance of the conditions laid down by the Commission, the latter shall issue the GBL2 after the payment of the prescribed fee, which is renewable every year.

There are no statutory requirements for a GBL2 company to have a secretary in Mauritius or otherwise. However, a corporation holding a GBL2 shall, at all times, have a registered agent in Mauritius who shall be a management company (§76 FSA).

2. Incorporation

An application for incorporation must be made through a licensed management company, and must be preceded with the reservation of a name with the Registrar. The application is then submitted to the Registrar, supplying the name of the proposed company, whether the company is to be limited or unlimited, whether the company is to be a private company, the proposed registered office, and the full name and address of each applicant, director and secretary of the company (§23).

Where the Registrar is satisfied that the application for incorporation of a company complies with the Companies Act and upon payment of the prescribed fees, the Registrar will (§24):

- enter the particulars of the company on the registers;

- assign a unique number to the company as its company number; and

- issue a certificate of incorporation in the prescribed form.

Global business companies may apply concurrently to the Commission to obtain either a GBL1 or GBL2.

The length of time for incorporation, registration and licensing of a new Mauritius entity is dependent upon whether it will be seeking a GBL1 or GBL2, the latter taking only 2-3 business days while the former up to 7-10 business days by the relevant regulatory bodies, once all the necessary documentation has been received and submitted. The incorporation process could take longer should either the Registrar or the Commission request additional documentation subsequent to the initial submission in the course of their consideration of the application.

3. Company Constitution

A certificate of incorporation is conclusive evidence that all the requirements of the Companies Act as to incorporation have been complied with and, on and from the date of incorporation stated in the certificate, the company is incorporated under the Companies Act (§25). A company incorporated under the Companies Act shall be a body corporate with the name by which it is registered and continues in existence until it is removed from the register of companies (§26) (see Part E: 4. below).

To simplify the registration process and the operation of companies, the Companies Act dispensed with the requirement that a company should have a memorandum and articles of association. However, a company may choose to have a constitution, although there is no statutory requirement to have one as the Companies Act comprehensively sets out the rights, powers, duties and obligations of the company, the board, and each director and shareholder (§41).

a. Constitution

Under a constitution, the company, the board, and each director and shareholder still have the same rights, powers, duties and obligations set out in the Companies Act, except to the extent that they are restricted, limited or modified by the company's constitution in accordance with the Companies Act (§40(1)). In effect, a company's constitution acts as a binding contract between (i) the company and each shareholder; and (ii) each shareholder, in accordance with its terms and provisions (§43). Where a company does not have a constitution, the rights, powers, duties, and obligations of the company, the Board, each director, and each shareholder of the company shall be those set out in the Companies Act (§41).

Where a company does not have a constitution, the shareholders may choose to adopt a constitution post-incorporation at any time by way of special resolution (§44(1)). Where a company already has a constitution, the shareholders may by way of special resolution, alter or revoke the constitution of the company (§44(2)). Shareholders, under the Companies Act, already benefit from enforcement rights and the ability to obtain remedies for breach of any constitutional provision. Companies incorporated prior to the commencement of the Companies Act may also retain their memorandum of association and articles of association as its constitution, but such companies are prohibited from altering any of the existing provisions unless and until the two separate documents are replaced by a single consolidated document which will thereafter be referred to as the constitution (§44(3)). Within 14 days of the adoption of a constitution by a company, or the alteration or revocation of the constitution by a company, the Board shall cause a notice in a form approved by the Registrar to be delivered to the Registrar for registration (§44(5)).

b. Objects

Under the Companies Act, a company is no longer required to state its objects, unless its constitution requires otherwise. However, if a company wishes to state its objects, then its business purpose will be restricted to those specific objects.

Subject to the Companies Act and to any other enactment, a company has full rights, powers, privileges and capacity to carry on or undertake any business or activity, do any act, or enter into any transaction from both within and outside Mauritius (§27(1)). The constitution of a company may contain a provision relating to the capacity, rights, powers, or privileges of the company only if the provision restricts the capacity of the company or those rights, powers, and privileges (§27(3)). Where the constitution of a company sets out the objects of the company, there is deemed to be a restriction in the constitution on carrying on any business or activity that is not within those objects, unless the constitution expressly provides otherwise. The Companies Act also provides that, notwithstanding any restrictions prescribed by the company's constitution on the business or activities in which the company may engage in, the capacity and powers of the company will not be affected by those restrictions and no act of the company will be invalid by reason only that it was done in contravention of those restrictions (§28(2)).

In addition, a person is not deemed to have notice or knowledge of the contents of a company's constitution (or any other document relating to a company) merely because the constitution (or document) is registered with the Registrar or is available for inspection at an office of the company (§30).

c. Names and Change of Name

The Registrar will not register a company under a name or register a change of the name of a company,, unless the name is available (§31). Furthermore, the Registrar will not reserve a name that is identical or almost identical to a name of an existing company, or so nearly resembles that name as to be likely to mislead, unless the existing company is in the course of being dissolved and signifies its consent for its name to be used to the Registrar (§35(1)). The Registrar will also not register a company with a name that includes the word "Authority", "Corporation", "Government", "Mauritius", "National", "President", "Presidential", "Regional", "Republic", "State", "Municipal", "Chartered", "co-operative" or "Chamber of Commerce", or any other word that the Registrar considers gives a suggestion of similar implication (§35(2)). In addition, the Registrar will not register a name that he considers offensive (§34(2)).

As the name reservation fee is solely applicable upon a successful reservation, there is no additional financial deterrent from trying to register a new name that was not originally accepted by the Registrar.

For all companies, other than global business companies, where the liability of the shareholders of the company is limited, the company name must end with the word "Limited" or "Limitee" or, their respective abbreviations, "Ltd" or "Ltee" (§32).

A company may, subject to its constitution, change its name by passing a special resolution, which must accompany an application to change the name of a company (in the prescribed form) and be further accompanied by a notice reserving the name (§36(1)). Where the Registrar is satisfied that the above requirements are satisfied, he will record the new name of the company, record the change of name on its certificate of incorporation and require the company to cause a notice to that effect to be published in such manner as the Registrar may direct (§36(2)). A change of name of a company will take effect from the date of the certificate and will not affect the rights or obligations of the company or any legal proceedings against the company (§36(3)).

A company must ensure that its name is clearly stated: in every written communication sent by, or on behalf of, the company; and on every document issued or signed by, or on behalf of, the company that creates a legal obligation of the company (§38(1)). It is important to note that where the name is incorrectly stated in a document which evidences or creates a legal obligation of the company and the document is issued or signed by or on behalf of the company, every person who issued or signed the document may, subject to exceptions, be liable to the same extent as the company (§38).

d. Amendment of Constitution

As stated above, the shareholders may alter the company's constitution at any time by way of special resolution (§44(2)). Companies incorporated prior to the commencement of the Companies Act may also retain their memorandum of association and articles of association as its constitution, but are prohibited from altering any of the existing provisions unless and until the two separate documents are replaced by a single consolidated document which will thereafter be referred to as the constitution (§44(3)). The board must file a notice of any adoptions, alterations or revocations with the Registrar within 14 days of the adoption, alteration or revocation taking place (§44(5)).

e. Fetter of Company's Power

Following the principles enunciated in the UK case of Russell v Northern Bank Development Corporation Ltd [1992] 3 All ER 588 (HL) a company is barred from contractually agreeing to fetter its statutory powers, i.e. those powers reserved to the shareholders. Thus, for example, a contract made by a company that it will not exercise its statutory power to alter its articles is deemed to be unenforceable.

This bar against the company fettering its statutory powers is not specifically included in the Companies Act. It is also important to note that section 27 provides that while a company has "full capacity to carry on or undertake any business or activity, do any act or enter into any transaction", these powers are expressed to be "[s]ubject to this Act, any other enactment" and "[t]he constitution of a company may contain a provision relating to the capacity, rights, powers, or privileges of the company only if the provision restricts the capacity of the company or those rights, powers and privileges". Accordingly, the constitution of a company may fetter the powers conferred to it by the Companies Act.

That being said, the Companies Act does provide that the company may not fetter its powers in certain instances. For example, and notwithstanding the constitution of a company, the following powers may only be exercised by the shareholders by special resolution (§105(1)):

- to alter, revoke or adopt a constitution of the company;

- to reduce the stated capital of the company;

- to approve a "major transaction";

- to approve an amalgamation; and

- to put the company into liquidation.

Apart from a resolution to put the company into liquidation, which may not be rescinded in any circumstances, a resolution concerning any of the above may only be rescinded by a special resolution (§105(2) and (3)).

f. Continuance and Discontinuance

i. Continuance

The Companies Act allows for the registration and continuation of foreign companies as any type of company admitted under the Companies Act providing: the company is permitted by the laws of its "home" jurisdiction to transfer its incorporation; the company has complied with the requirements of that law in relation to the transfer of its incorporation; and, where that law does not require the shareholders (or a specified proportion of them) to consent to the transfer, the transfer has been consented to by not less than 75% of the shareholders and 21 days notice of the meeting specifying the company's intention to transfer was given to the shareholders (§297). However, a foreign company may not be registered and continue: where it is in the process of winding up or liquidation; where a receiver or manager has been appointed, whether by court order or not, in relation to the property of the company; or where there is a scheme or order in force in relation to the company whereby the rights of the creditors are suspended or restricted (§298).

In all circumstances, a foreign company may not be registered as a company in Mauritius unless it can satisfy a solvency test immediately after becoming registered.

An application for a foreign company to continue into Mauritius is made by filing the following documents with the Registrar (§296):

- a certified copy of the certificate of incorporation or other such document that evidences the incorporation of the company;

- a copy of the resolution authorising the continuation of the company in Mauritius;

- a certified copy of the documents containing its constitution;

- a statement of the charges on the company's assets;

- documentary evidence which satisfies the Registrar that the above requirements in relation to the laws of the "home" jurisdiction have been satisfied;

- the documents and information that are required to incorporate a company if it were being a newly incorporated company under the Companies Act;

- documentary evidence which satisfies the Registrar that the company is in good standing in the country of its incorporation and in the countries in which it has any significant activity; and

- such other document or information as may be required by the Registrar.

Upon receiving a properly completed application and on being satisfied that the requirements for registration under the Companies Act have been complied with, the Registrar will enter on the register of companies the particulars of the continuing company and issue a certificate of registration in the prescribed form (§299(1)). Once issued, the certificate of registration constitutes conclusive evidence that all the requirements of the Companies Act pertaining to registration have been complied with, and that the continuing company is now registered as from the date of registration specified in the certificate (§299(2)).

It is important to note that no new legal entity is created as a result of a continuing company becoming registered in Mauritius, and the identity of the body corporate constituted by the continuing company or its continuity as a legal entity will not be prejudiced or affected. The property, rights or obligations of the continuing company will not be affected nor will any proceedings by or against the continuing company (§300).

ii. Discontinuance

Mauritian companies may also transfer their corporate entity to other jurisdictions, and thereby be removed from the register of companies for the purposes of becoming registered or incorporated under the law in force in, or in any part of, another country (§301).

A Mauritian company is prohibited from applying for discontinuation out of Mauritius where: it is in liquidation or an application has been made to the Court to put the company into liquidation; a receiver or manager has been appointed, whether by a Court or not, in relation to the property of the company; or the Mauritian company has entered into a compromise with creditors or a class of creditors (§305(1)). Furthermore, a company cannot be removed from the register unless it can satisfy the solvency test immediately before its removal (§305(2)).

A company may only apply to be removed from the register of companies if the application has been approved by a special resolution of the shareholders (§303). The application by a discontinuing company for its removal from the register of companies must be made in a form approved by the Registrar and must be accompanied by (§302):

- documentary evidence which satisfies the Registrar that all of the above has been complied with;

- documentary evidence which satisfies the Registrar that the company has given public notice stating that it intends after the date specified in the (not being less than 28 days after the date of the notice) to apply for discontinuance for the purpose of becoming incorporated under the laws of another country (and specifying that country);

- written notice from the Commissioner of Income Tax and the Commissioner for Value Added Tax that there is no objection to the company being removed from the register;

- documentary evidence which satisfies the Registrar that the company is to be incorporated under the laws in force in another country; and

- such other document or information as may be required by the Registrar.

Upon the Registrar receiving an application satisfying all the requirements under the Companies Act, the Registrar will issue a notice removing the discontinuing company from the register. The discontinuing company will only be deemed to be removed from the register once that notice is registered under the Companies Act (§306).

The removal of a discontinued company from the register of companies does not result in the identity of the body corporate or its continuity as a legal person being prejudiced or affected. The property, rights, or obligations of that body corporate as well as any proceedings by or against it will not be affected. Likewise, proceedings that could have been commenced or continued by or against a discontinuing company before it was removed from the register may be commenced or continued by or against the body corporate that continues in existence after its removal from the register (§307).

4. Management and Administration

a. Registered Office, Registered Agent and Management Company

Every company must have a registered office in Mauritius to which all communications and notices may be addressed and which shall constitute the address for service of legal proceedings on the company (§187(1)). Global business companies must also have the name of its management company or its registered agent, as the case may be, and the words "Registered Office" displayed permanently in a conspicuous place in legible romanised letters on the outside of its registered office (Fourteenth Schedule, Part I, paragraph 15).

GBL1 Companies must, at all times, be administered by a management company and (§71(5) FSA) and all GBL2 companies must have a registered agent in Mauritius, which must be a management company (§76(1) FSA). A registered agent is responsible for providing such services as the company may require in Mauritius including the filing of any return or document required under the FSA and the Companies Act; and the receiving and forwarding of any communications from, and to, the Commission or the Registrar (§76(2) FSA). A registered agent will be subject to such obligations in relation to appointment, change of registered address or registered agent, and such other matters for the purpose of the above, as may be prescribed (§76(3) FSA).

b. Constitution

See Part A: 3.a. above.

c. Requirements for Officers or Representatives in Mauritius

As stated above, a GBL1 company must have a minimum of one company secretary, who must be a natural person ordinarily resident in Mauritius (§163), although a corporation may act as secretary with the approval of the Registrar and subject to certain specified conditions (§164). It is worth noting that the Companies Act also provides that a secretary shall have certain duties, such as providing the Board with guidance as to its duties, responsibilities and powers (§166). There are no statutory requirements for a GBL2 company to have a secretary in Mauritius or otherwise.

d. Directors

While the Companies Act decrees that the director(s) of a company (together the "Board") are responsible for and shall have all the powers necessary for managing, directing or supervising of the business and affairs of the Company (§129(1)), there is no precise definition under Mauritian law as to who is a "director". The Companies Act defines the term as including "any person occupying the position of director by whatever name called" and this definition includes an alternate director but does not include a receiver (§128).

Subject to any limitations in the company's constitution, the business and affairs of a company are managed by its Board (§129). An important point to note is that despite the power of the Board to manage the affairs of a company, a company is restricted from entering into a "major transaction" unless it has been approved by a special resolution of the shareholders, or is contingent on a special resolution being passed (a major transaction being defined as one that will result in an increase or decrease of assets, liabilities, rights or interests equal to 75% or greater of the company's assets prior to such a transaction) (§130). However, investment companies holding a GBL1 may enter into major transactions without having to obtain the approval of the shareholders, and the shareholders of any private global business company may, by unanimous resolution, agree that the above requirements relating to major transactions do not apply (Fourteenth Schedule, Part I, paragraph 11).

The first directors of a company are those persons named in the application for registration or amalgamation proposal (§135(1)). All companies must have at least one director who is ordinarily resident in Mauritius (§132) and that director must be a natural person (§133(1)). These requirements are waived, however, for GBL2 companies, i.e. non-resident and corporate directors are permitted (Fourteenth Schedule, Part II, paragraph 1). A person must not be appointed as a director unless that person has consented in writing to be a director and certified that he is not disqualified from being appointed or holding office as a director of a company (§134).

The Board may, subject to the Companies Act and the company's constitution, delegate some of its powers to a committee of directors, a director or employee of the company, although the Board remains responsible for the exercise of the power by that delegate as if the Board had directly exercised the power itself (§131). However, it should be noted that the Companies Act provides for a list of powers of the director which cannot be delegated (Seventh Schedule).

Directors may be appointed by ordinary resolution of the shareholders, unless the company's constitution otherwise provides (§137). A director of a public company may be removed from office by an ordinary resolution passed at a meeting called for the purpose that includes the removal of that director (§138). A director of a private company may only be removed from office by special resolution of the shareholders passed at a meeting called for that purpose (§138(2)).

Under the Companies Act, where a company has only one shareholder (who is also the director of the company) for a continuous period of 6 months, the sole shareholder/director must file a notice with the Registrar nominating a person to be the secretary of the company in the event of the death of the sole shareholder and director (§140(3)). This provides a very useful succession mechanism for sole shareholder/directors.

It is worth noting that under the Companies Act, the acts of a person as a director will still be valid even though that individual's appointment was defective or the individual was not qualified for appointment as a director (§141).

Global business companies must keep a register of directors containing (Fourteenth Schedule, Part I, paragraph 3(1)):

- the names and addresses of the persons who are directors;

- the date on which each person whose name is entered on the register was appointed as a director; and

- the date on which each person named as a director ceased to be a director.

The Board must give notice to the Registrar in the approved form of any change in the directors or the secretary of a company, or of any change in the name or the residential address of a director or secretary (§142(1)). The notice must contain the following details (§142(2)):

- the date of the change;

- the full name and residential address of every person who is a director or secretary, or person nominated where the company has only one shareholder/director; and

- the form of consent and the certification that the new director or secretary is not disqualified from being appointed as director or secretary.

The notice must be delivered to the Registrar within 28 days of the change. Where the Board fails to comply with the above requirements, every director and any secretary will have committed an offence and will be liable to a fine (not exceeding 200,000 rupees) (§142(3)).

i. Director's Duties

The duties of directors have been extensively codified in the Companies Act such that every director, in exercising his powers and discharging his duties, must, inter alia (§143(1)):

- exercise their powers in accordance with the Companies Act and within the limits and subject to the conditions and restrictions established by the company's constitution;

- obtain the authorisation of a meeting of shareholders before doing any act or entering into any transaction for which the authorisation or consent of a meeting of shareholders is required by the Companies Act or by the company's constitution;

- exercise their powers honestly in good faith and in the best interests of the company and for the respective purposes for which such powers are explicitly or impliedly conferred;

- exercise the degree of care, diligence and skill required that a reasonably prudent person would exercise in comparable circumstances (§160); and

- not agree to the company incurring any obligation unless the director believes at that time, on reasonable grounds that the company shall be able to perform the obligation when it is required to do so;

- account to the company for any monetary gain, or the value of any other gain or advantage, obtained by them in connection with the exercise of their powers, or by reason of their position as directors of the company, except remuneration, pensions provisions and compensation for loss of office in respect of their directorships of any company which are dealt with in accordance with section 159 of the Companies Act;

- account to the company for any monetary gain, or the value of any other gain or advantage, obtained by them in connection with the exercise of their powers, or by reason of their position as directors of the company, except remuneration, pensions provisions and compensation for loss of office in respect of their directorships of any company which are dealt with in accordance with section 159;

- not make use of or disclose any confidential information received by them on behalf of the company as directors otherwise than as permitted and in accordance with section 153;

- not compete with the company or become a director or officer of a competing company, unless it is approved by the company under section 146;

- where directors are interested in a transaction to which the company is a party, disclose such interest pursuant to sections 147 and 148;

- not use any assets of the company for any illegal purpose or purpose in breach of paragraphs (a) and (c), and not do, or knowingly allow to be done, anything by which the company's assets may be damaged or lost, otherwise than in the ordinary course of carrying or its business;

- transfer forthwith to the company all cash or assets acquired on its behalf, whether before or after its incorporation, or as the result of employing its cash or assets, and until such transfer is effected to hold such cash or assets on behalf of the company and to use it only for the purposes of the company;

- attend meetings of the directors of the company with reasonable regularity, unless prevented from so doing by illness or other reasonable excuse; and

- keep proper accounting records in accordance with sections 193 and 194 and make such records available for inspection in accordance with sections 225 and 226.

These duties are coupled with the overriding requirement that every officer (which includes director or secretary) must "exercise the powers and discharge the duties of his office honestly, in good faith and in the best interests of the company; and the degree of care, diligence and skill that a reasonably prudent person would exercise in comparable circumstances" (§160(1)).

The Companies Act provides that directors, when exercising their powers and performing their duties, are entitled to rely upon the reports, statements, financial data, other information prepared or supplied, and on professional or expert advice given by:

an employee, but only where the director believes on reasonable grounds that the employee is reliable and competent; a professional adviser or expert, where the director believes the matter is within their professional or expert competence; and another director, or a committee of directors in which the director did not serve, in relation to matters within the director's or committee's designated authority (§145(1)). The above only applies, however, where the director acts in good faith; makes proper inquiry where the need for inquiry is indicated by the circumstances; and has no knowledge that such reliance is unwarranted (§145(2)).

A director will be in breach of his duties to the company if: the director competes with the company; becomes a director or officer of a competing company (§143(1)(h)); or uses information about the company that he came across as a result of his role in the company (§153(1)(d)), unless the company specifically approves such actions in accordance with the Companies Act, e.g. a form of resolution which has been circulated to all the members and is signed by 75% of all members entitled to attend and vote at a meeting of shareholders (§146).

In addition, a director who has information which would have been only obtainable through his directorship, must not disclose that information to any person, or make use of or act on that information, except (§153):

- for the purposes of the company;

- as required by law;

- in any circumstances authorised by the company's constitution;

- when approved by the company; or

- when authorised by the Board to a person whose interests the director represents or a person in accordance with whose directions or instructions the director may be required or is accustomed to act in relation to the director's powers or duties (subject to the director recording such particulars in the interests register where it has one).

The Board may authorise a director to disclose or make use of information"where it is satisfied that to do so is not likely to prejudice the company" (§153(3)). Further, any monetary gain made by a director from the use of information which the director could have only obtained through his position as a director, must be accounted for to the company (§153(4)).

The Companies Act also responds to the potential for conflict confronting directors in group company structures and joint venture scenarios. In doing so, the Companies Act has extended the duties of directors beyond the traditional principle that fiduciary duties are owed only to the company. The Companies Act (§143(2)-(4)) provides for the following:

- A director of a company that is a wholly-owned subsidiary may, when exercising powers or performing duties as a director, if expressly permitted to do so by the constitution of the company, act in a manner which he believes is in the best interests of that company's holding company even though it may not be in the best interests of the company.

- A director of a company that is a subsidiary, other than a wholly-owned subsidiary, may, when exercising powers or performing duties as a director, if expressly permitted to do so by the constitution of the company and with the prior agreement of the shareholders (other than its holding company), act in a manner which he believes is in the best interests of that company's holding company even though it may not be in the best interests of the company.

- A director of a company incorporated to carry out a joint venture between the shareholders may, when exercising powers or performing duties as a director in connection with the carrying out of the joint venture, if expressly permitted to do so by the constitution of the company, act in a manner which he believes is in the best interests of a shareholder or Shareholders, even though it may not be in the best interests of the company.

The Companies Act also provides that the above duties are owed to the company and not to the shareholders, debenture holders or creditors of the company (§143(5)(a)). In addition to a derivative action (see Part A: 6.n.ii below) or any other lawful remedy available to a shareholder, any member or debenture holder may apply to the Court for: a declaration that an act of transaction, or proposed act, by any director constitutes a breach of any of their fiduciary duties under the Companies Act; and an injunction to restrain any director from doing any proposed act in breach of their fiduciary duties (§143(5)(b)).

Directors also have a duty to call a Board meeting where they believe that the company is unable to pay its debts as they fall due, to consider whether the Board should appoint a liquidator or an administrator (§162).

ii. Director's Interests

The Companies Act provides for a number of situations where a director may, either directly or indirectly, be materially interested in a transaction (§147(1)(a) to (e)). A director must disclose to the Board the fact that he may have a monetary or other interest in a transaction entered into by the company, as soon as the director becomes aware of that fact (and make an entry into the interests register, if the company has one) (§148(1)), unless the transaction is between the director and the company and is made in the ordinary course of business and on usual terms and conditions (§148(2)).

A failure by a director to comply with the above requirements will not affect the validity of a transaction entered into by the company or the director (§148(4)), though the transaction may subsequently be avoided by the company provided it does so within 6 months after the transaction is disclosed to shareholders, e.g. by the company's annual report or otherwise (§149(1)), unless the company received "fair value" under the transaction (§149(2)). It is a rebuttable presumption that the company received "fair value" if the transaction was entered into on usual terms and conditions and in the ordinary course of its business (§149(4)). The avoidance of such a transaction will not affect the title or interest of a third party in or to property which that person has acquired where the property was acquired from a person other than the company for valuable consideration, and without knowledge of the circumstances of the initial transaction (§150).

Subject to the company's constitution, a director who is interested in a transaction entered into, or to be entered into, by the company, may (§152):

- in the case of a public company, not vote on any matter relating to the transaction;

- in the case of a private company, vote on any matter relating to the transaction provided he disclosed his interest in accordance with §148 of the Companies Act;

- attend a meeting of directors at which a matter relating to the transaction arises and be included among the directors present at the meeting for the purpose of a quorum;

- sign a document relating to the transaction on behalf of the company; and

- do any other thing in his capacity as a director in relation to the transaction, as if the director was not interested in the transaction.

The Companies Act provides for situations where a director must disclose matters relating to a share dealing by directors and, in certain situations, a director is restricted in dealing in shares of the company. For more specific advice, please refer to the contact details at the end of this Guide.

iii. Indemnities and Insurance

A company is prohibited from indemnifying or insuring for costs incurred by a director (or employee) in defending or settling any claim or proceedings relating to any liability for any act or omission of the director (or employee) when acting in his capacity as director (or employee) except in accordance with the Companies Act, and any such indemnity given will be void (§161(1) and (2)). This restriction does not apply where liability is to a person other than the company (or related company), unless the liability is criminal in nature or it is in respect of a breach of fiduciary duty (§161(5)). Subject to its constitution, a company may indemnify a director (or employee) of the company (or a related company) for any costs incurred by him or the company in respect of proceedings that relates to liability for any act or omission of a director (or employee) in his capacity as a director (or employee), provided judgment is given in the director (or employee's) favour (§161(3)).